By Alejandro Chavarria, NH Senior Database Developer

I grew up in Ketchikan in Southeast Alaska, often visiting a beautiful lake and picnic area near my house called Ward Lake. It’s a popular place for swimming, kayaking, fly fishing, picnics, BBQs, and trails. Recently, I learned about a dark piece of its history that feels important to share, especially in honor of Indigenous People’s Day which we recently celebrated on October 14th. I myself am Tsimshian Alaska native, but Alaska is a vast territory with many different peoples and cultures that are closely tied to their land. The Tsimshian people traditionally inhabited Southeast Alaska and British Columbia, Canada. But I’d like to talk about the Unangax people that traditionally inhabited a very different part of Alaska: the Aleutian Islands.

Ward Lake in Ketchikan, Alaska today. It is a popular place for swimming, kayaking, fly fishing, picnics, BBQs, and trails.

The Unangax (sometimes also referred to as “Aleuts”) were forcibly relocated to 5 different sites in Southeast Alaska during World Ward II, one of which was Ward Lake in my hometown. It was meant to be for their own protection due to Japanese attacks on their islands, but it was very poorly planned and executed leading to a lot of death and disease, as well as the loss of their homes and culture.

In 1942, Japan bombed and occupied several of the Aleutian Islands. They even took some Unangax people to Japan as prisoners of war. In response, the United States government decided to evacuate the Unangax people from their homes. Villagers were given only a few hours’ notice to leave. They could bring only one suitcase per person and had no idea where they were going.

People were given very little notice of the evacuation, could take very few personal belongings, and were packed in ships where there was not enough room to keep the sick separated leading to the spread of illness and in some cases, death.

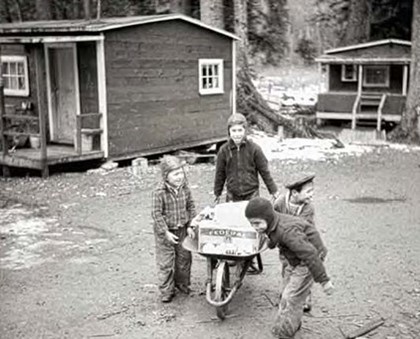

Before arriving at Ward Lake, they had to live in schools and Army tents on a nearby island for a couple of weeks. They were told they had to help build their own boat to be towed to Ward Lake. Ward Lake already had housing for 65 people as part of a depression-era jobs program, but 163 refugees arrived—more than double the capacity. The Unangax people had to build additional housing themselves. In the meantime, they slept on floors or in Army tents. The new cabins had makeshift roofs and no siding to protect from the weather.

One survivor described arriving at Ward Lake as feeling like being put in prison. There was only one building with running water where they took showers—a new practice for them, as they were used to steam baths and bathing in tubs. There was also only one kitchen where meals were cooked with government-provided food, including low-quality salmon. They were also unable to continue their subsistence lifestyle without their usual gear or boats and in a new and unfamiliar setting with different plant and animal life.

Cabins built by the refugees can be seen in the background. They didn’t have adequate roofs or siding to protect from the weather

Despite being near the main town for employment and goods, medical care was hard to access. Sanitation wasn’t good, and many people became sick. There was a lot of death and disease. They also faced backlash from community members who didn’t like that their favorite swimming area was taken over. Looking at all this makes it painful to realize that some of the 4 other communities the Unangax were taken to actually had worse conditions than at Ward Lake.

In all, over 10% of all the Unangax refugees died during this time. The U.S. Forest Service started tearing down the camp at Ward Lake even before the refugees left to return home. The entire camp was completely torn down shortly after and hardly any evidence of its existence remains today.

The Unangax people were given only $12 per person by the government for the hardships they endured and this was only for those that survived. Over 40 years later, the remaining survivors received an official apology from the government and $12,000 each. Some money was also provided to help rebuild their home villages.

Despite these hardships, the Unangax culture is alive and well today, thanks to the efforts of people who saw the importance of revitalizing and nurturing it. A YouTube video titled “See How Unangax Culture and Dance Resurrected, Despite WWII Internment Camps” shows how one community worked to revive traditional dance, music, language, and arts which inspired other communities in the area. Elders who remembered the old ways are teaching the younger generation and the younger generation are creating new music. Watch the video here: https://youtu.be/C4I9aOxLAUo?si=2ESlkI8V2fKApqKI.

Sources:

- https://akhistory.lpsd.com/articles/article.php?artID=215

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aleutian_Islands_campaign

- https://www.nps.gov/aleu/learn/historyculture/removal-maps.htm

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/aleu-mobley-ch-7.htm

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/aleu-mobley-intro.htm

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/aleutian-voices-forced-to-leave.htm

- https://www.teaguewhalen.com/ward-lake

- https://youtu.be/C4I9aOxLAUo?si=2ESlkI8V2fKApqKI